She smiles not because she is happy, but because she’s been promised happiness.1

Ev Baczewska

Physiotherapy as a type of ‘cruel optimism,’ “…promises to induce in you an improved way of being” (Berlant, 2011, p. 1). When the spectre of ableism lingers, the cruel optimism of physiotherapy as the gateway to improved bodily function, or in its most radical form – the mere possibility of being in close proximity to able-bodiedness – leads to a preoccupation with unachievable somatic norms. The cruelness rests in the unattainable fantasies this optimism conjures. This entry will chart the traumas of ableist tendencies reflecting on the failure of the promises of happiness, and recount the “depression, dissociation, pragmatism, cynicism, optimism, activism, [and] an incoherent mash” (Berlant, 2011, p. 2) associated with the conscious unravelling of this cruel optimism.

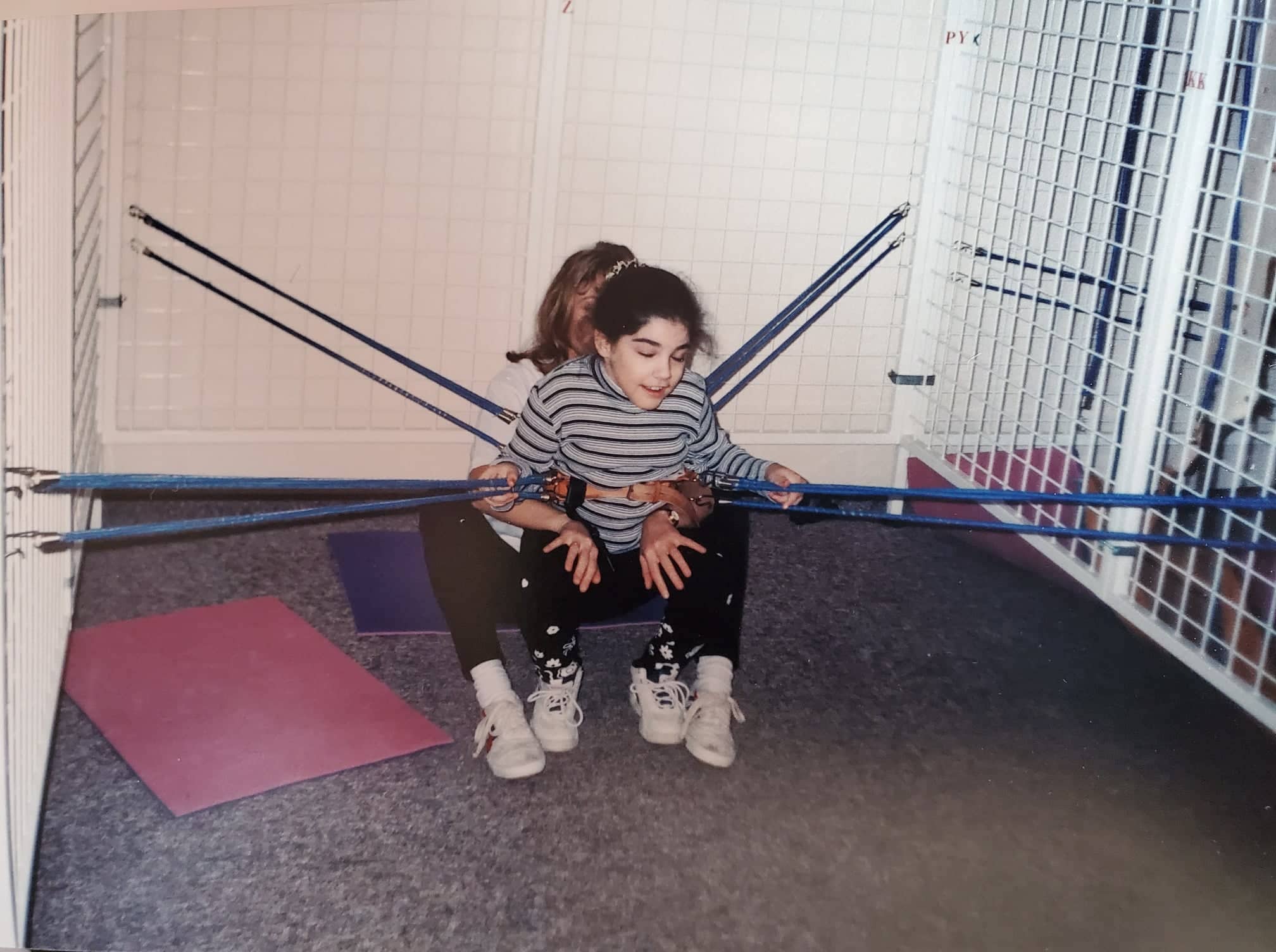

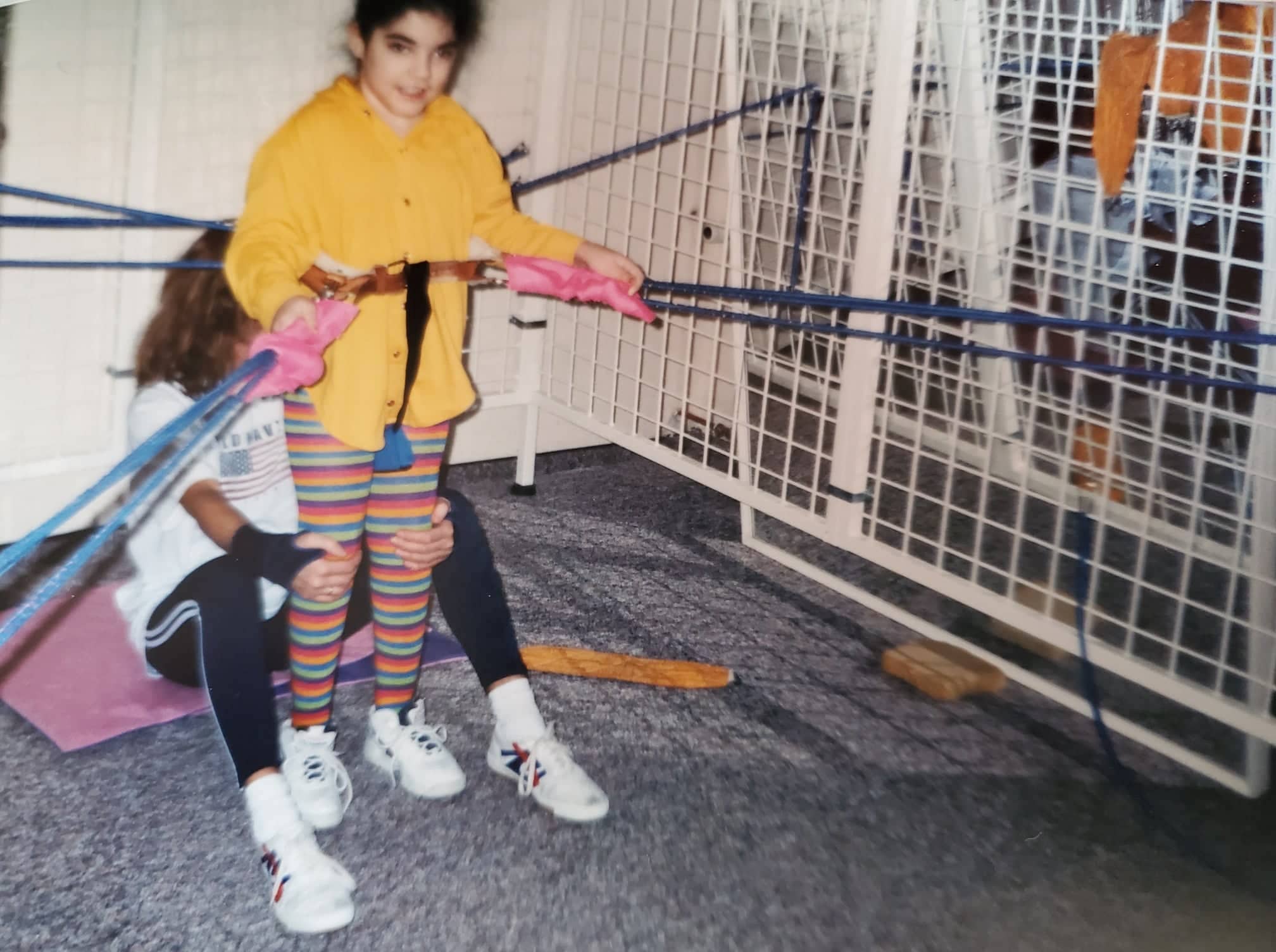

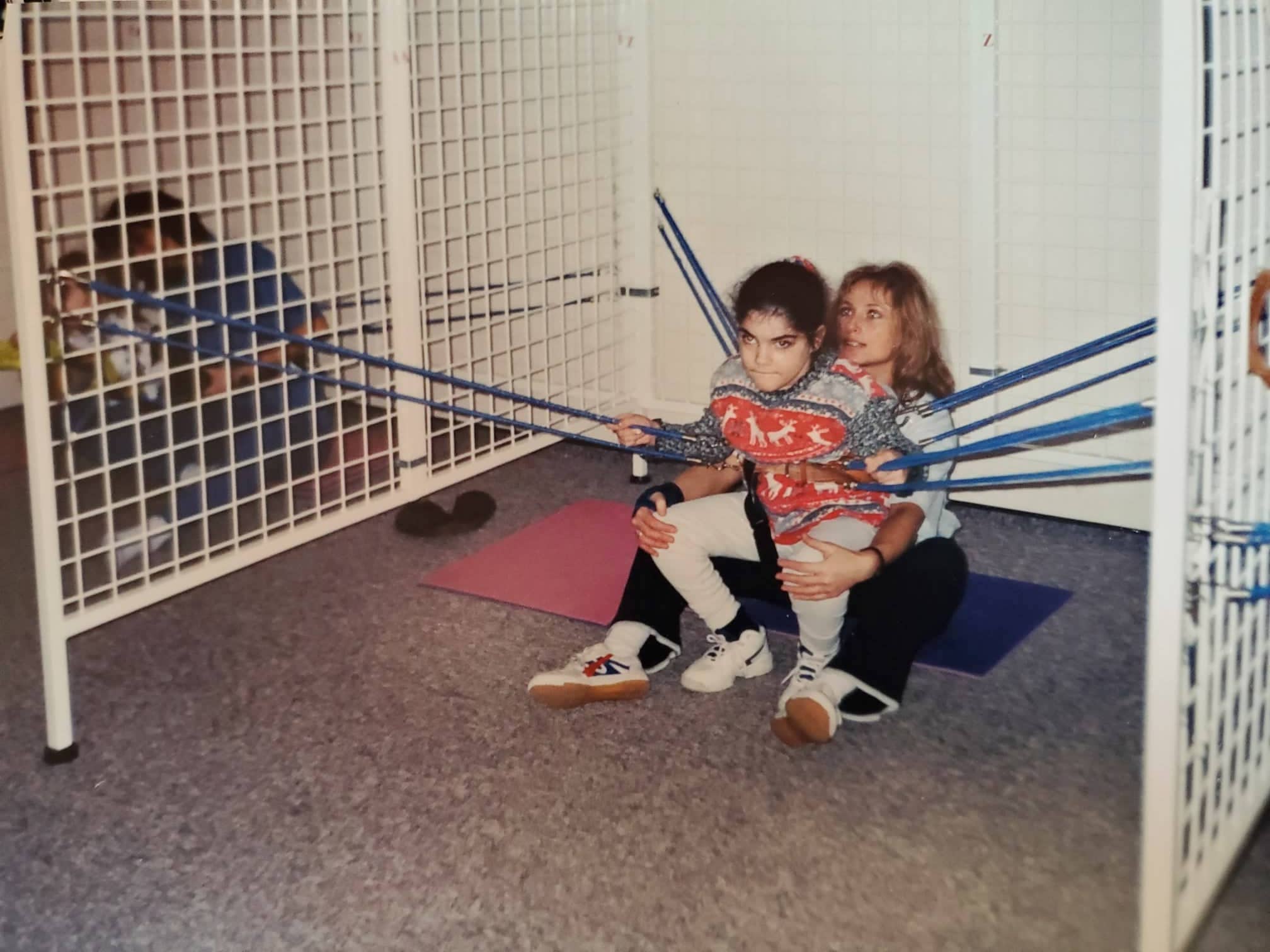

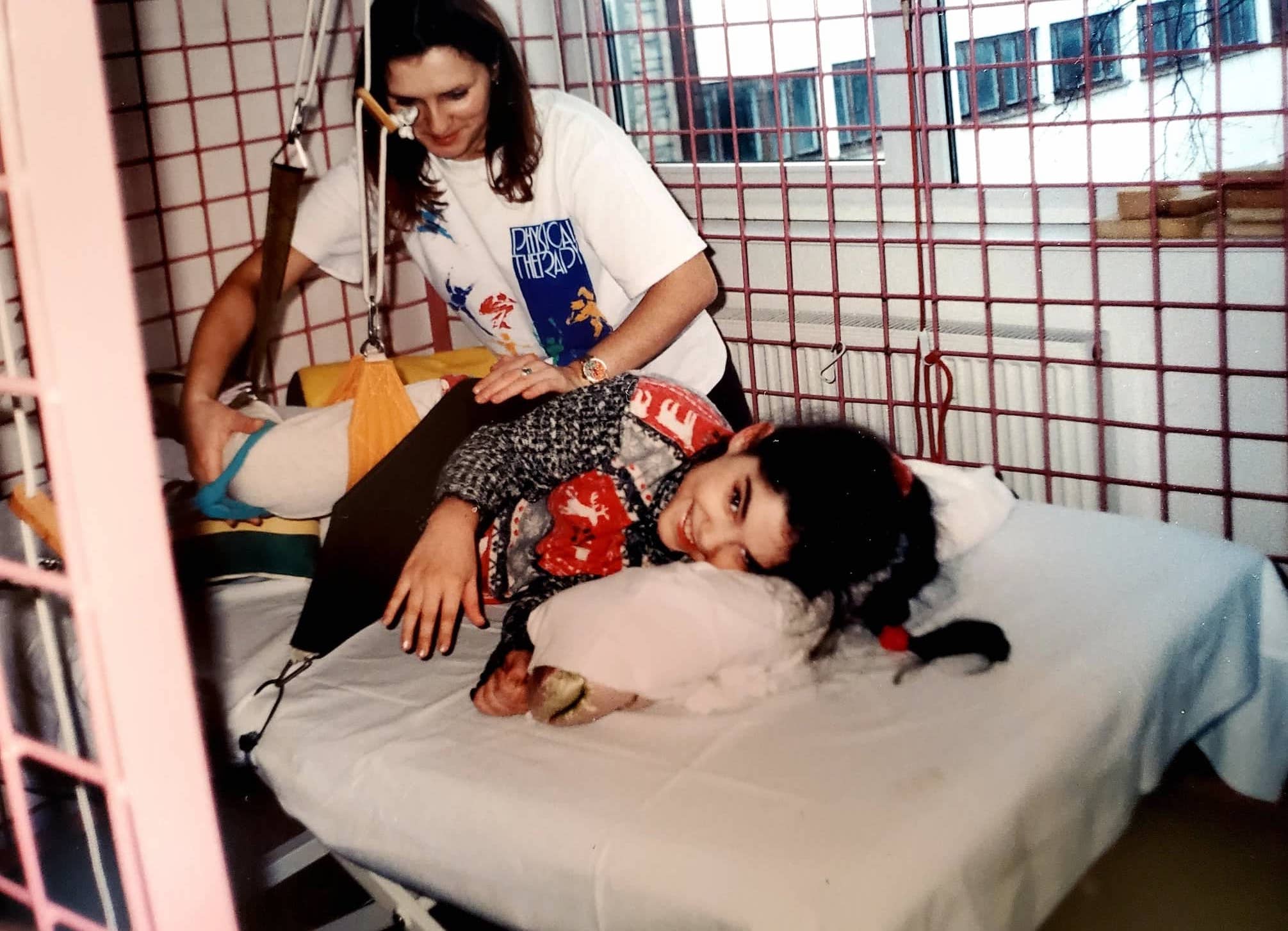

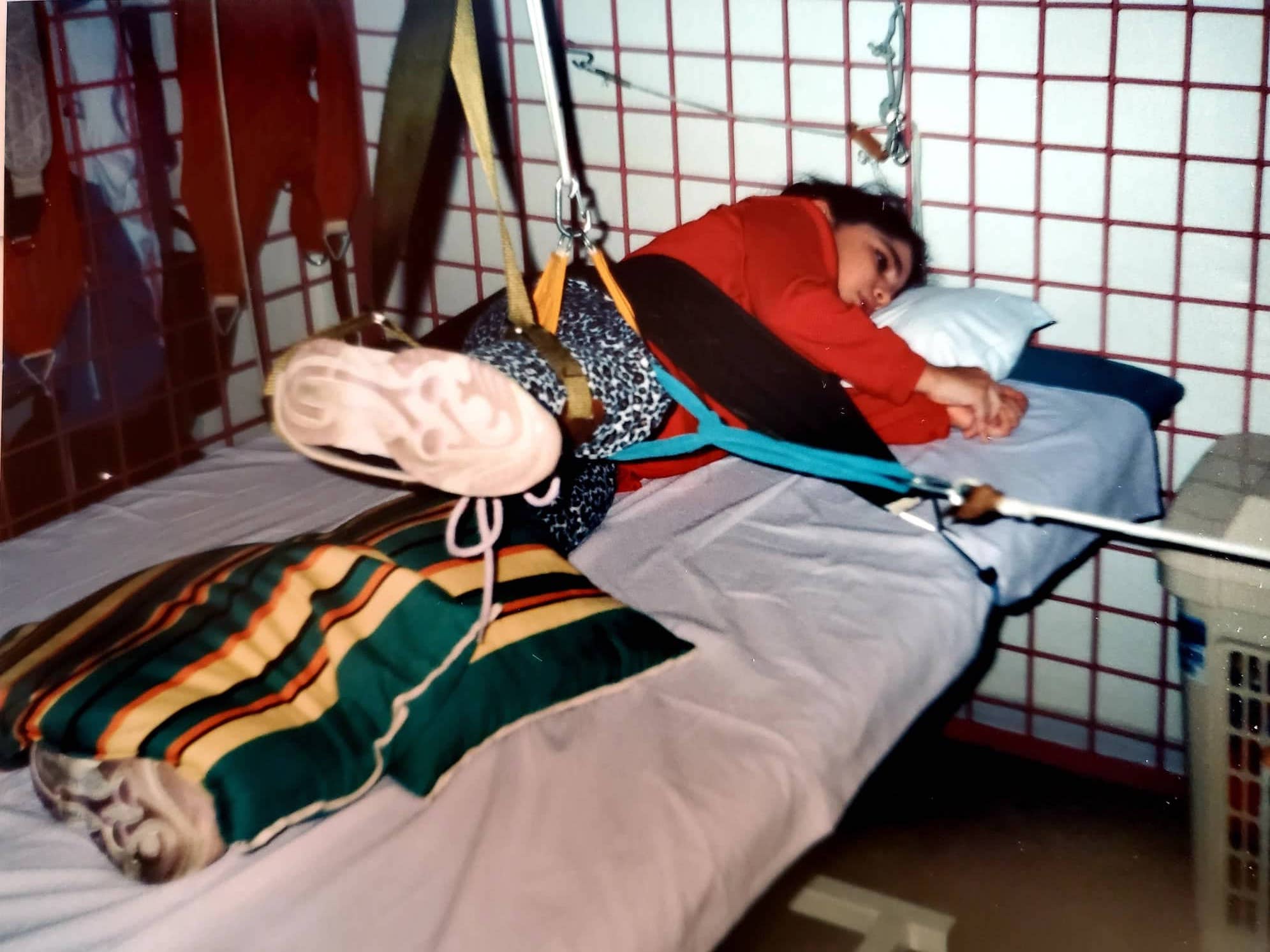

Personal photograph collection. Taken circa 1998/1999, images document my experience at the Euromed Rehabilitation Centre in Poland.2 Some photographs feature my wearing the ADELI Suit (in more recent iterations known as the EuroSuit, an improved version of its predecessor).3

“A relation of cruel optimism,” Berlant (2011) writes, “exists when something you desire is actually an obstacle to your flourishing” (p. 1). It rests on a preoccupation with an often correlated socially desired outcome. This relation is not fundamentally cruel, but can potentially become so when the desired objective is informed by an unrealistic and unattainable guiding force.

Ableism as guiding force: physiotherapy = (proximity to) ablebodiedness = happiness.

According to Ahmed (2010), if happiness is a prescriptive directive that orients us toward the right ways of being, then it moves us towards or aligns us with objects, persons, ideas, and worlds that we gather around us as a happiness building project. Happiness is not something we simply disire, but “what you get in return for desiring well” (p. 37). It is in this way that happiness can be thought of not as a state of being, but “what it does” (p. 15): how it moves us by what it promises.

The promise of happiness has brought me in close proximity to multiple worlds, each valuing ablebodiedness as the ultimate happiness building project, expecially for a child diagnosed with Cerebral Palsy of the spastic quadriplegia4 variety. Happiness as a project of will (Ahmed, 2014): willing the right way, being willing to subject oneself to certain unpleasantries for the promise of future happiness, positions physiotherapy or the greater enterprise of orthopaedics as an alignment of will. Deriving from two words: orthos “correct or straight” and paidion “child,” combined, orthopaedics involves the process of straightening the child (Ahmed, 2014, p. 72). (The concept of using the rod to straigten the child would haunt me well into adulthood, and bring with it new and complex meaning). A good child, a willing child is a malleable child. Following this injunction, a disabled child with willful limbs must be willing to be physically manipulated into acceptable forms of being. By extension, a disabled child is a happy child when they are agreeable to physical intrusion and manipulation because they are in pursuit of transforming their willful, rigid bodies into willing and able bodies. Ableness as an achivement of will, an outcome of desiring well.

In a world built and sustained on monopolizing ablebodiedness, you desire what you encounter. By continually encountering the world as easier to navigate and primarily accessible to ablebodied walkers, happiness correlates with ease of access in its myriad of forms (access to love, belonging, the privilege of valued personhood, etc.). Even as a child, I was acutely aware of ablebodiedness as a vital precondition to the claim of femininity and the essence of attractiveness.

With the effects of my disability manifesting in asymmetrical and increased muscle tone and tension, achieving a necessary degree flexion or extension results in (en)countering resistence. This resistance can be painful. Getting all limbs and muscles to activate and maintain the dynamics of movement requires the application of force. Such force is both physical (applied to the body) and reactive (felt through the body). It is effective (corporeal: of the body) and affective (incorporeal: not itself of the body) (Massumi, 2002). The quest for ableism is a force to be reckoned with. The force at once real, material, quantifiable, and spectral. The spectre of ableism lingers in the (phantom) promises of happiness it solisits (maximum independence = happiness). It is in this manner that the optimism of ableism as the guiding force acquires its cruel currency.

Being the daughter of Polish parents, I was granted access to claim dual-citizenship: Canadian and Polish. The capacity to cross borders expanded physio(therapeutic) options. Thus, the quest for (proximity to) ablebodiedness became a transnational pursuit. My parents underscored the contrast between the philosophy informing physiotherapy practices employed on young children in Poland and those employed on children in Canada and the US: The former praised for using preemptive methods in treating disability, the latter described as employing reactionary methods mitigating the effects of disability. This is a matter of perception, of course, and not a matter of objective assessment that would withstand any measure of scientific scrutiny. Such comparisons are banal and uninformed – they overlook the complex forces developing bodies are subjected to in an attempt to cure and denounce disability. Both methods sustain the unattainable guiding principle of self-mastery equating to happiness. Such precarious correlations continue to reify systems of oppression exercised on the body reinforcing feelings and forms of abjection (Taylor, 2018) directed toward oneself.

A smile as performative consent.

I have retained vivid memories of my fear of being institutionalized as a child because of my disability. Intermittently, from age 2.5 onward, I was enrolled in various medical and therapeutic sessions, programs, institutions, and interventions meant to intervene (come between me and the progression of disability) as a preemptive and proactive approach. Age 9 marks the last of these institutionalized forms of in-patient interventions of my childhood.

Investing financial and emotional energy in the future promise of my happiness by maximizing my independence, strength, and endurance, my parents enrolled me in a 4-week physiotherapeutic session in a seaside town in Poland (See introductory photo collage and footnotes for further information). Looking at these photographs now, I am struck by the number of photographs which feature my smiling. This time is vividly punctuated by feelings of exhaustion and pain, interspersed with the hope and optimism of being in proximity to happiness (I may not leave here transformed into an independent walker sans mobility devices, but I will come close). These are the phantom limns that highlight, contain and unify the photographic series above. Retrospectively reframing this experience, I am smiling because I have been promised happiness, I am willing in the right way. I am an obedient, disabled child doing what is expected, what I am obligated to do (this pursuit has been financed, it is expensive. I will not waste it). Here, a smile is a performative form of consent or consent by proxy: the proxy is not a person, but a promise. I am not consenting to the pain, exhaustion or discomfort, but the happiness they may bring if I am willing to do everything that is expected. My mom would often caution the physiotherapy team: She may (silently) cry but she is a brave child, a willing child – she is always willing to try. I may have cried, but I smiled more often. A smiling child is a willing child.

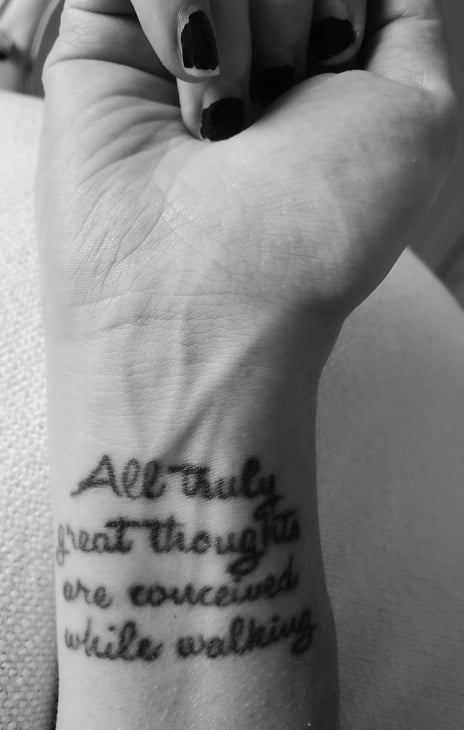

In the end, my 9-year old understanding of my body and definitions of success informed by ableist tendencies, deemed the 4-week physically daunting happiness building endeavour as a failure: I returned with mobility devices in tow. I may have been more independent, had stronger core stability, improved dynamic movement and balance, but these gains were eclipsed by preconditions of success correlated with independent walking. Thus ensued a lengthy lapse in any physiotherapy or consideration of the well-bing of the physical body. This was a form of defiance and dissociation. I was a willing child, never whining; I was a compliant child, rarely complaining. My expectations never came to fruition: I failed. It wasn’t until age 23 that I entered a local out-patient physiotherapy setting. This time, my physiotherapist being more intuitive, would caution his students or colleagues tasked with working with me: You really have to watch her. She won’t tell you, she smiles, but her smile masks pain.

My body: What will can’t accomplish, the rod must

Patient has undergone an extensive spine surgery with the imposition of titanium instrumentation with screws from T9-S2 across the pelvis, multiple-level facetectomies and bilateral laminectomies [as well as] diskectomies In addition, patient has undergone interbody fusion with bone grafting for correction of a severe spinal deformity.

Patient surgical report (March 2018)

My increasing resentment toward my body led to apathy toward any further physiotherapeutic intervention. I was disappointed, disinterested, and disillusioned. I didn’t want to contribute any further focus to my (disabled) body – the cause and site of my oppression. My deliberate disinvestment became a compensatory method: what the body couldn’t accomplish, the mind would compensate for. All time and energy was devoted to academic and educational accomplishment. Without critical self and social reflection, I was reproducing the systems that subjugate the body in favour of the mind. This is an affective example of superficial disembodiment. It is the relationship that we foster with ourselves as bodies that sustains the capacity for violence imposed on bodies (Taylor, 2018).

Beginning in early adolescence, I (along with my parents) began to notice my propensity to lean to one side. Just as everyone grows accustomed to inhabitng their bodies in certain ways and positioning at certain angles relative to comfort and ease of performing certain tasks, I became accustomed to my dominant side. The effects of gravity and weakened bone, coupled with asymmetrical muscle tone, became the perfect alchemy for the slow but steady progression of a spinal curve. This was something I ignored until it was impossible to – it was undoubtedly painful, but even worse to me – it became visible. It further impeded balance, walking, and overall function, but it was its visibility that was the most shameful to me: yet another manifestation of disability – a visible deformity. It was at the point of pronounced visibility that my parents and I began the reciprocal assigning of culpability of who was more at fault for the stark curvature of a once straight spine. They blamed me: I didn’t sit straight, even after being repeatedly cautioned and reminded. I refused physiotherapy – I did this to myself. I blamed them: I was young. It was their responsibility to monitor progression. They blamed themselves: we spared the rod that spoiled the child. We should have been insistent in our resolve in the pursuit of orthopedic intervention (See Ahmed, 2014 for further discussions of the concept and cultural significance of using the rod to straighten a disobedient child’s will). What the spared rod didn’t accomplish in childhood, will now have to reside within the adult.

At age 29, the decision to expose myself to a medically imposed trauma was largely guided by socio-cultural expectations of the body that are founded on ableist tendencies – this I admit with a sense of trepidation. As someone who is dedicated to deconstructing forces of ableism (i.e., the belief that disabled bodies are in need of fixing or straightening to lead a happy and fulfilling life), I was surprised by the scripts I would employ in my effort to convince surgeons of my candidacy for such an intrusive procedure. Sensing their hesitation, I became strategic in framing my primary reasoning for risking some very undesirable outcomes. For instance, I would always focus on the functional gains this procedure would likely render possible. Truthfully, my willingness was guided just as equally by function as it was by form (bodily aesthetics). Although, procedures of anthropotechnology5 increasingly render the distinction between form and function difficult to sustain.

view.

Recognizing the individual body as a socially intelligible object, it is from a learned sense of abjectness and shame that I arrived at an affirmative decision despite being reminded of the risks and consequences associated with the correction of such a deformity. Confident in my ability to withstand the medical violence I was eager to subject my body to, I didn’t dedicate much thought to the initial physical and emotional effects of spinal reconstruction. The introduction of titanium to the organic substance of the body sent it into shock – an internal rage that manifested itself in extreme muscle tone and tension. As a reaction to the enormous stress imposed on the spine, the body clenched and locked into place only leaving the neck and head under my full, independent control. This resulted in an alienation I did not bargain for. I found myself mourning the body I once was – the same one I felt chronic shame and disgust towards, coupled with chronic discomfort and pain. Nevertheless, it had been a chronic source of pain and discomfort I had learned to live with, even grown accustomed to. I knew how to accommodate and compensate for how I previously moved. The reconstruction, however, presented me with the necessity to find a new centre of gravity – both quite literally and figuratively speaking.

The feelings of alienation from myself were further deepened by what Coffey (2018) terms ‘body work.’ Focused on “altering the subjective experience of the body” (p. 55), constant body work was punctuated by body talk. Recalling previous benchmarks by which to measure surgically mediated improvement signaled “a conscious investment in the appearance in function of the body” (p. 55). The objective was to turn a volatile, rigid body to a willing and functional body, now improved by surgically imposed instrumentation. This is a key demonstration of the ways in which frameworks of mastery, power and dominance over the human body continue to operate. Whereas, historically they were meant to subjugate the physical body under the control of a master (consider practices of colonialism), modern thought has rebranded this framework under the guise of liberalism, self control, or sheer will power and strength of character in overcoming the body’s limits.

The process of becoming acclimated to the titanium residing among muscle, nerve, and bone, etc. demanded unlearning old movement patterns. With time, effort, and a recovering spirit, I moved my way back to joy and away from alienation. I find joy in my ability to take a walk outside around the neighbourhood – this was never possible in my adulthood as the outdoors was an uncontrolled environment that was too expansive to attempt with my deformed spine. Whereas walking was previously confined to indoor spaces, I am now able to claim the privilege of the symbolic value of scuffed and wet shoes – it signals a recontouring of my biographical landscape. Accepting the foreign objects that are now part of my being also required an active reconceptualization of the self: I am now equally body, memory, soul, spirit, muscle, flesh, bone, and all the stuff of life – I am titanium.

Reframing physiotherapy as radical self love

In The Body is Not an Apology, Taylor (2018) frames self-love as central to the advancement of social justice. If systems of oppression thrive on our inability to value “corporeal diversity,” (Ahmed, 2014, p. 51), we must understand social justice “as a call to open up a world that has assumed a certain kind of body as the norm” (Ahmed, 2014, p. 51). Taylor’s (2018) concept of radical self-love is fundamentally different from self-acceptance. Whereas self-acceptance implies what Ahmed (2014) calls “smoothing a relation” (p. 51) or learning to navigate a system based on oppression, radical self love demands the elimination of oppressive forces and hierarchies founded on bodily or social markers of difference.

If childhood is marked by the learning and internalizing of systems of norms that inform our relation to the world (i.e., ablebodiedness as achieving happiness), my adulthood has been marked by the unlearning or the consciousness unraveling of the cruel optimism informed by toxic, “precarious, and perverted” promises of happiness (Ahmed, 2010, p. 44). My approach is now rooted in practical, pragmatic objectives guided by critical perspectives of the forces of ableism. Physiotherapy was once a happiness exploit focused on the cure or overcoming of disability. To will the body in the right way, I was expected to share in the conditioned abjectness toward my being. I now share in a collective refusal to reaffirm a bodily hierarchy that contributes to the oppression of people with disabilities. I have since actively reclaimed the ways in which I use, value, and care for my body. No longer focused on curing but on caring, my entry into a physiotherapy clinic has become a portal. A portal through which I enter regularly. A scheduled and welcomed liminality between chronic disability and pain punctuated by temporal relief, even if fleeting. A portal within which space collides with time. In her memoir, Engle (2023) curates an archive of medical, social, cultural understandings of chronic conditions to limn a life lived in pain. She narrates her experience of entering this kind of portal. Her description so vividly reflects my re-articulation of the affective experience of physiotherapy:

The passage between the building’s main entrance to her office door was a portal to another dimension. I lay on the table and knew her interest lay not in fixing me but in providing temporary succour. Time melted in that room.

p. 85. (Emphasis added)

Engle poignantly argues that although chronic and often excruciating, pain is ordinary, although deeply affecting, alienating, or disabling. Valuing bodily diversity contributes to a movement, a new world building project made possible by expanding our biographical narratives, landscapes, and understandings of disability beyond interests in cures. Often impossible, notions of curing lead to self-abject, or peddle unrealistic expectations of transcending disability or wrongly framing pain and disability as opportunities for personal growth. Disability is a natural aspect of life. If you’re not disabled in the present, you will experience disability in the future. We all share in the necessity to grow and build a world where our collective understandings of disability begin with acceptance of our vulnerability.

Until next time.

With vulnerability & shared refusal,

Ev XO

Footnotes.

1 In The Promise of Happiness (2010), Sara Ahmed charts a happiness archive in which happiness functions as a social imperative. Happiness is linked with certain life choices and the avoidence of others. To align yourself with social norms and acceptable desires will lead to happiness. To be happy means to be properly aligned with gender, somatic, heteronormative, etc. expectations. Happiness, thus becomes a project of will. Veering away from norms promising happiness results in killing joy.

2 To learn more about the in-patient, multi-therapy methods used at the Euromed Rebilitation Centre for children living with neurological phyisical disabilities, please visit their website: https://euromed.pl/en/pioneering-methods-of-rehabilitation/

3 To learn more about the EuroSuit and its therapeutic objectives, please visit: https://euromed.pl/en/eurosuit-2/

4 Cerebral Palsy spastic quadriplegia is characterised by increased muscle tone (spasticity) in all four limbs, and the trunk. Such spasticity results in rapid muscle contraction and release, limited range of motion, and joint stiffness. Combined, these contribute to poor balance and coordination, difficulty walking, and other varied musculoskeletal effects. For example, prolonged increased muscle tone (muscles continuously pulling on bones and joints) can result in the development of bodily deformities.

5 The process of introducing technology to the natural or organic environment. The methodology of intervention meant to improve various forms of life.

References.

Ahmed, S. (2014). Willful subjects. Duke University Press.

Ahmed, S. (2010). The promise of happiness. Duke University Press.

Berlant, L. (2011). Cruel optimism. Duke University Press.

Coffey, J. (2018). Body work: Youth, gender and health. (Youth, Young Adulthood and Society Series). Routledge.

Engle, K. (2023). Chronic conditions. McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Massumi, B. (2002). Parables for the virtual: Movement, affect, sensation. Duke University Press

Taylor, S. R. (2018). The body is not an apology: The power of radical self-love. Barrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc.