All truly great thoughts are conceived while walking.

Friedrich Nietzsche, Twilight of the Idols

Walking as practical, as perennial, as pretheoretical – arising prior to theoretical scrutiny or consideration. Walking justified in the Nietzschean sense as an ordinary activity that precedes theory, but serves as the motility through which theory is derived. Thus: truly great theory = the capacity to walk. Walking as exposure. Walking as experience. Walking as a philosphical exercise (consider the Socratic Method or the Socratic Walk).

Despite increased urbanization of the contemporary city and new methods of mobility (i.e., the automobile, bike riding, public transportation, etc.), walking remains “part of the mobility reportoire of hypermobile people” (Shortell, 2016, p. 3) engaging in the pedestrian hustle and bustle. Walking as the main signifier of the modern cityscape is a demonstration of self-mastery and active citizenship. In fact: micro-mobility practices (everyday walking), reveal the instrumental and intentional patterns of the everyday citizen as they navigate space for profit and for pleasure. Thus, walking as an everyday practice becomes a banal exercise of human agency – to walk is to take command of space. It is a tactic “used by the relatively powerless aginst the designs of the relatively powerful” (Shortell, 2016, p. 2). Consider pound the pavement politics in the form of street protests or demonstrations.

Walker as ordinary practitioner, modern rebel.

The performance of walking in a culture preoccupied with ambulatory navigation as a demonstration of agency codes walking as one of the ultimate signifiers of what it means to be human. Common literary archetypes of modern navigation go as far as positioning the city walker “as an exemplar of rebellion, freedom, and agency – the pedestrian hero or the flâneur” (Cresswell, 2010, p. 20). De Certeau (2002), in his Walking in the City theoretical-literary piece, further describes walkers as ordinary practitioners. He writes, “the ordinary practitioners of the city live ‘down below,’ below the thresholds at which visibility begins. They walk – an elementary form of this experience of the city; they are walkers” (p. 93).

However, the act of walking being labeled as ordinary, everyday, is problematic and not always accurate. As a disabled person whose everyday navigation of the world requires the use of assistive devices, unassisted walking practices are not ordinary. Walking being codified by walkers as normal, pedestrian, and seamless, results in my being positioned as the “‘implicit ‘other’ who supposedly live[s] outside the ordinary, the everyday […]” (Highmore, 2001, p. 1). Claiming everyday life as self-evident and easily accessible based on the navigation patterns of the pedestrian serves as an implicit erasure of my struggle. The persistence of building ‘back door’ (Dolmage, 2017) accessibility routes over front door universal access, reifies disability as something that must be hidden from view. The wheelchair user is not a prominent figure of the modern cityscape. In fact, it is through back door accessibility that my entrance becomes front door spectacle. My attendence is not expected, but impossible to ignore as it sometimes requires the rearrangement of the space.

Thus, ambulatory negotiation of space – the capacity to walk is in and of itself a privileging act. The inability to independently walk is a structural limitation that becomes spatially evident because a preoccupation with walking leaves little support for other modes of everday mobility. As such, different forms of movement as enacted and exercised by the body become intelligible markers of difference that inform subjectivity and intersect with those of race, class, gender, etc., to produce unique experiences of oppression and privilege.

If we consider the usage of something as a form of communication (Ahmed, 2019), the modern city was discernably built for able-bodied walkers. The prominent presence of stairs, the absence of curb cuts at the end of sidewalks signifies the lack of consideration for assistive mobility device users. The presumed presence of the able-bodied walkers is so banal that “walking is very much hiding in plain sight” (Shortell, 2016, p. 2). What is common recedes from view, unless it prevents ease of passage (Ahmed, 2019, 2017). Walking as a display of modern city life, Cresswell (2010) writes, “is wrapped up in narratives of worthiness, morality, and aesthetics that constantly contrast it with more mechanized forms of movement which are represented as less authentic less worthy, less ethical” (p. 20).

Being confronted with inaccessible city spaces and finding alternative routes from Point A to Point B (often short routes for the able-bodied walkers), become forced detours for wheelchair users dictated by the absence of smooth or level terrain. The absence of level pavement or presence of stairs is not coinsidental, it is a claim of the indended user and whether the terrain was meant to be used at all. In appraising the usefulness of something or for whom use was intended, “what is missing comes to matter” (Ahmed, 2019, p. 88 emphasis in original). It is an absent presence, a spectre, a moral imperative.

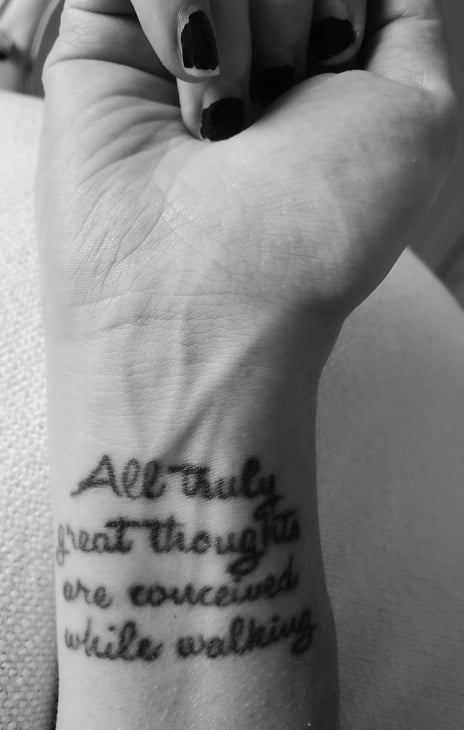

Struggling to find value in the way I move in the world, recurrent metaphors, archetypes, and everyday practices that privilege walking served as willful incentive to inscribe the Nietzschean quote (introducing this entry) on my inner right-hand wrist:

All truly great thoughts are conceived while walking.

As a sign of protest (not an ordinary walker, but still a rebel), the clenched fist rises again (see Ahmed, 2017, Living a Feminst life). As a refusal to accept walking as ordinary, I wear this quote as a badge of irony that it poses in my life. An attempt to queer the meaning of this quote, it is inscribed on a disabled woman’s wrist. It is a rearticulation of my biographical landscape – my theories of everyday life are borne out of my necessity to queer walking practices as a form of survival.

The aesthetics of motion…

My reflection eternally haunted by the generalized other.

I sit at the opposite end of the uncanny valley – my body and my mind real,

but the aura of the real, the desired is betrayed not by physical appearance,

but by movement, the aesthetics of motion.

Ev Baczewska

Until next time.

With vulnerability & shared refusal,

Ev XO

References

Ahmed, S. (2019). What’s the use: On the uses of use. Duke University Press.

Ahmed, S. (2017). Living a feminist life. Duke University Press.

Cresswell, T. (2010). Towards a politics of mobility. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 28:17-31.

De Certeau, M. (2002). Walking in the city in The Practice of Everyday Life. University of California Press. pp. 91-110.

Dolmage, J. T. (2017). Academic ableism: Disability and higher education. University of Michigan Press.

Highmore, B. (2001). Questioning everyday life in The Everyday Life Reader. Routledge. pp. 1-34.

Shortell, T. (2016). Introduction: Walking as urban practice and research method in Walking in Cities: Quotidian Mobility as Urban Theory, Method, and Practice. Temple University Press. pp. 1-16.